This article is published in Aviation Week & Space Technology and is free to read until Jun 06, 2024. If you want to read more articles from this publication, please click the link to subscribe.

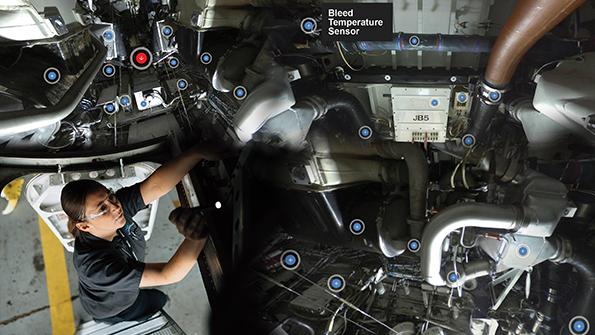

PSA Airlines has developed several technologies to improve technician training, including this Virtual 360 Aircraft tool.

Any Inside MRO reader knows the aftermarket is suffering from a significant workforce shortage. Boeing’s Pilot and Technician Outlook projects a global need for 690,000 new technicians over the next decade—125,000 of them in North America alone. Consultancy Oliver Wyman predicts the region will have a shortfall of more than 48,000 MRO staff by 2027, and the Aviation Technician Education Council’s 2023 Pipeline Report says U.S. commercial aviation will be 31,000 mechanics short by 2031.

During the Aviation Technician Education Council’s (ATEC) annual conference in Tucson, Arizona in mid-March, stakeholders discussed industry efforts to ramp up workforce growth and highlighted key challenges that are holding back the pipeline of qualified workers.

Although the FAA issued 2.7% more mechanic certificates in 2022 than in 2021, ATEC reports that only half the graduates of airframe and powerplant (A&P) schools took the agency’s mechanic exam that year. In addition to barriers such as fear of testing, inadequate preparation and test costs, speakers at the ATEC conference highlighted two major issues contributing to the low number.

First and foremost, the U.S. is experiencing a shortage of FAA-certified designated maintenance examiners (DME). According to ATEC member surveys, nearly one in every five A&P schools has reported problems with a lack of DMEs—even schools with their own DMEs on staff.

At Tarrant County College in Fort Worth, the aviation maintenance technology (AMT) program previously had five instructors who were also DMEs, but two have since retired or given up the position. “Currently, we have three instructors on staff who are also DMEs, and these guys are past retirement age, so there is definitely a shelf life,” Program Coordinator Darrell Irby said. “We brought this issue up with our [Flight Standards District Office] and had several additional instructors apply for it, but nothing’s happened at this point. We’re really fearful that at least two of our DMEs are going to retire pretty soon, and we won’t be able to cover all the testing.”

According to Rob Cush, legislative affairs director for the Aircraft Mechanics Fraternal Association, the U.S. had about 700 DMEs before the COVID-19 pandemic, but this number shrank to 67 post-pandemic. “It’s crazy,” he said. “You’re asking kids to wait months upon months and to travel to neighboring states because there’s no DME in their location.” He added that DMEs are prohibited from crossing state lines to test students.

Jared Britt, director of global aviation maintenance training at Southern Utah University and a certified DME, points out that he and one other DMEs must service a 1,000-mi.2 area between three states due to a shortage in the region. “Students have to drive to me, spend the night, test with me all day and drive home, and that’s an expense for them,” he said. “And I’m a busy guy—I can’t do six tests in a week, although students need that.”

ATEC’s Pipeline Report notes that the U.S. will need nearly 30% more DMEs to accommodate all AMT school graduates. In response, ATEC’s legislative committee is lobbying for a revision to the FAA’s organization designation authority program to allow schools or industry partners to manage FAA testing delegates to meet student demand. It is also recommending adjusting DME qualifications and eliminating geographic limitations.

Although the barriers to testing have clearly limited the number of AMT students opting to take their A&P exams, ATEC reports that 10% of graduates are skipping testing due to job offers that do not require certification. As the MRO industry becomes more desperate for staff, companies are beginning to hire graduates who only hold repairman certificates, and airlines are starting to hire and train mechanics right out of school instead of waiting for them to cut their teeth at an MRO provider. One regional carrier at the conference reported that around 54% of its maintenance workforce has less than one year of experience.

Before 2020, Alaska Airlines required at least five years of industry experience to be hired into its maintenance operations, according to Technical Training Manager Buck Gaines. “After COVID, everybody started hiring, and by 2022, the experience levels just evaporated all around. We’re seeing folks with 1-2 years’ experience coming in,” he said.

Bombardier Network Training Manager Eamonn Powers reported a similar trend. “We used to not hire anyone that had less than 5-10 years’ experience. We used to never hire noncertified technicians—it was probably less than 10%, and most were structures guys,” he said. “Now we’re in a crunch to find applicants and good people that are able to work on the floor Day 1. We had to be a bit more creative with how we bring these people on.”

Bombardier launched a two-year apprenticeship program in February with WSU Tech at its Wichita site. The OEM took its ATA-based curriculum and mirrored it to the FAA’s Airman Certification Standards to provide a linear career path for people who have not attended an A&P school. Bombardier has already brought on eight apprentices and plans to expand the program further.

“The simplest goal is: ‘How do I hire a person that has basically no experience and get them billing time rather quickly? How do we do that in a way that maintains our very high safety expectations but doesn’t put an overburden on the operation itself?’” Powers said. Students who complete the apprenticeship program will earn not just their A&P license, but also Bombardier credentialing that qualifies them to perform maintenance tasks on the company’s aircraft.

Alaska’s previous onboarding maintenance training procedures were based on new hires with 3-5 years’ experience. Over the past six months, it has partnered with A&P schools from which it recruits to begin offering basic general familiarization training on Boeing 737NG and MAX aircraft to prepare them for platforms they will encounter at Alaska or other airlines. To enable access to OEM intellectual property, the airline worked with Boeing to offer an offline version of its Maintenance Performance Toolbox system on iPads with which students can work. “It reduces technical risk for us, and it reduces the lead time to get them up to speed to get them in the operation,” said Phil Coop, maintenance technical training instructor at Alaska.

Meanwhile, PSA Airlines has revamped its new-hire training strategy to incorporate hands-on learning sooner and prioritize subjects where the airline sees the most technical issues, such as pneumatic bleed leaks or door pressurization problems. PSA has also implemented a YouTube-inspired video training platform and a Virtual 360 Aircraft tool that gives users a complete 360-deg. view of specific areas of an aircraft, which features information about components and will soon feature hyperlinks to its relevant training videos.

ATEC’s legislative committee is pursuing several other initiatives to address workforce pipeline issues. The council estimates that less than 10% of military veterans with aviation maintenance experience transition to similar civilian careers, so it is pushing for a simpler process to enable veterans to obtain their A&P licenses.

ATEC told Inside MRO in January that a shortage of qualified maintenance instructors is creating challenges for A&P schools. In March, it launched its ATEC Academy initiative to help aviation industry professionals transition to the classroom. Participants in the three-month hybrid course receive training in such areas as active teaching strategies, lesson planning, student behavior management, assessment and evaluation methods.

As part of the latest FAA Reauthorization bill, ATEC has also pushed to increase grant funding for MRO schools and organizations. Funding recipients can put the money toward a range of things, including training equipment and scholarships. Last year, the bill offered $10 million apiece for pilot and mechanic workforce initiatives. Cush said ATEC expects the new bill to increase this funding to $15-20 million for both career paths.